Naturally unique

The habitats of the Wadden Sea are a fascinating demonstration of how physical forces and biological activities interact to generate conditions for life in a fragile environment. They form a complex system across environmental gradients of depth and salinity, height and dryness, exposure to hydrodynamics and winds, and substrates modified by organisms. Here, you can find an invaluable record of past and ongoing dynamic adaptation of plants, animals and their coastal environments to global change. Despite the fragility, productivity of biomass is one of the highest in the world and offers wide food availability for fish, shellfish and birds.

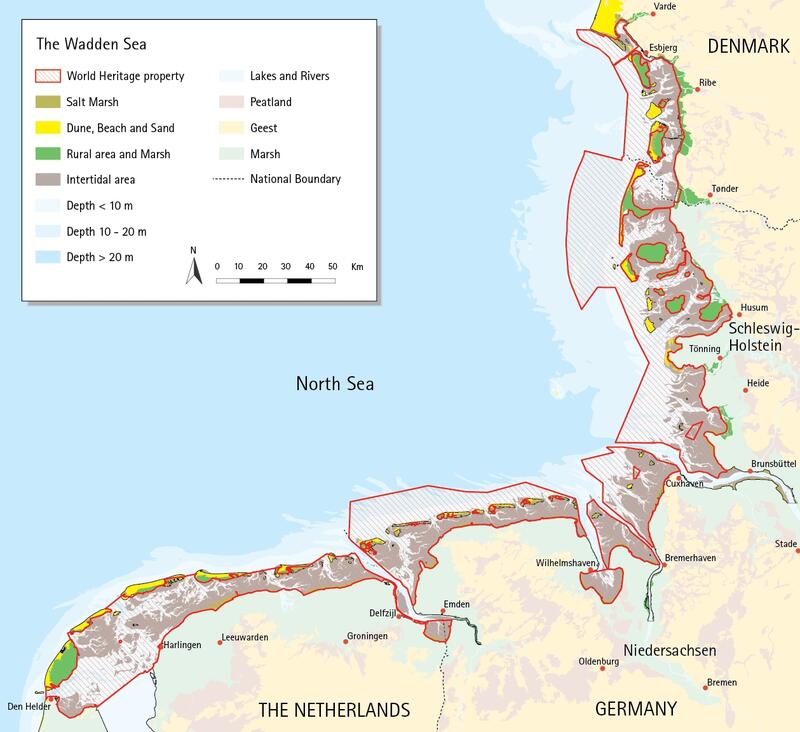

The Wadden Sea’s major habitats are arranged along an offshore-inshore gradient. They range from deep tidal inlets up to the highest dunes.

Map of the Wadden Sea and its major habitats. © CWSS.

Offshore belt

Transition from mudflat to offshore area. © CWSS/Bostelmann.

The offshore belt of the Wadden Sea has no tidal flats and drops off smoothly towards the open North Sea. There is a continuous exchange of both water and sediment with the tidal area. The sediment supply from the offshore belt is vital for the resilience of the coast when responding to changes in tidal area, sea level and to disturbances caused by storm surges.

Phytoplankton blooms often grow in this belt because turbidity is low enough for sufficient light and nutrient concentrations are high. Through the tidal channels and inlets this offshore primary production reaches the inshore zoobenthos. Also larvae of benthic fauna and fish drift from the offshore belt further inshore. Shrimp, fish, diving birds, seals and harbour porpoises readily commute between offshore and inshore zones.

Tidal area

Mudflats. © CWSS/Bostelmann.

The tidal area covers the most characteristic habitats of the Wadden Sea - the tidal flats, subtidal shoals and gullies of the back-barrier regions.

Twice a day, land slowly rises from the sea before it becomes again engulfed by the flooding waters. At low tide, the bottom of the sea meets the horizon and invites the observer to take a walk on the exposed tidal flats, covering over half of the tidal area. Caution is advised, however, as numerous runnels, some creeks and deep gullies intersecting the tidal flats may block the way.

The tidal flats may look desolate, but they are full of life. The sediment surface is almost completely covered with microscopic algae and bacterial colonies. Intertidal sea grass beds may also accumulate fine particles. Hidden from view are the lugworms – the gardeners of the tidal flats and with about one billion individuals the largest worm population worldwide. The lugworm’s continuous recycling of surface sediments keeps a sand flat sandy and prevents it from becoming a mud flat. In their secret work, lugworms recycle the upper layer of the sediment 10-20 times per year. With their help the anoxic sediment is enrichened with oxygen, which increases bacterial activity. All the lugworms leave behind are the eye-catching “spaghetti hills” – faecal mounds with coiled strings of sand.

The other half of the tidal area is covered by subtidal shoals and deep gullies which branch into ever smaller creeks and runnels across the tidal flats. They serve as a refuge for the intertidal fauna when conditions become harsh. With ebbing tide, young crabs, shrimp and fish in particular migrate to the subtidal area and return with the next flood. Sponges, tunicates and colonial hydrozoan polyps are mostly confined to subtidal shoals. The subtidal fringe and low intertidal zone are the primary sites for beds of suspension feeders, mussels and oysters in particular. Mussels attach to each other, accumulate sediment over the years and successively provide habitats for more and more species, until in a severe storm or a winter floes of ice scour it all away.

Estuaries

Estuarine natural habitats in a shallow side-arm of the Weser River. © Bioconsult.

The Wadden Sea is influenced by five main estuaries: Varde A in Denmark, Eider, Elbe and Weser in Germany and the Dutch-German Ems estuary. Estuaries are tidally influenced transition zones between marine and riverine environments. Usually, estuaries and deltas constitute the main coastal wetlands. In the Wadden Sea, however, estuarine habitats are present but not a dominant feature. They are rather small in size relative to the marine parts of the Wadden Sea.

Nonetheless, they are highly relevant to the Wadden Sea ecosystem, because they supply riverine inputs such as nutrients and toxic substances. They are also pathways for diadromous fish such as flounder, smelt and eel. And they form a specific habitat characterised by a strong variability of salinity, tidal range and turbidity inhabited by various obligate brackish-water species.

Different to the Wadden Sea World Heritage site, however, the estuaries have been strongly altered by human activities and only some parts are protected as nature reserves.

Salt marshes

Green beach on Amrum. © Martin Stock / LKN-SH.

Lovingly called “Neptun’s Garden”, salt marshes form the transition zone between sea and land. They are naturally open grasslands with habitat-specific plants of great beauty and diversity. Salt marshes can be rich in flowers, they can exhibit a diverse mixture of specialised plants and generalists adapted to disturbed regimes, or they can be completely dominated by one or two grass species.

In general, diversity increases from the regularly flooded pioneer zone to the rarely submerged upper salt marsh belt. The most specialised salt marsh plants can be found in the lower zone, while the upper salt marsh includes widely tolerant generalist plants that can also be found outside salt marshes. The salt marsh plants use different methods to adjust to salinity. For example, some regulate the salt content in their cells; others dispose salt-enrichened leafs.

Every flooding of the salt marshes leaves behind sedimentation, which causes the habitat to grow with time. Thus, salt marshes largely persist to sea level rise, growing at a similar rate.

Beaches and dunes

Sand transport on Rømø. © Martin Stock / LKN-SH.

Beaches and coastal dunes together constitute one habitat system. Sand blown in the landward direction from the dry parts of beaches becomes trapped by various pioneer plants forming embryonic dunes. Above the height of 20 m, wind forces become too strong for marram grass to slow down sand transport, and bare migrant dunes arise. These usually travel from west to east in response to the prevailing wind direction. The spectacular dunes on the barrier islands are evidence of this ongoing contest between aeolian mobilisation of sand and biotic stabilisation. Migrant dunes may reach the lee side of barrier islands, supplying beaches and tidal flats there with new sand. With a few exceptions (e.g. Eiderstedt peninsula, Skallingen) the dune habitat is confined to the Wadden Sea barrier islands.

Ecologically, beaches and dunes are linked to the other habitats, not only by sand transport but also by birds, which rely on beaches and dunes for foraging, nesting and resting habitats. Two red-list bird species prefer to nest on plains of dissipative beaches and among cusps of reflective beaches: Kentish plover and little tern. Their survival is threatened because unfortunately they prefer the same beaches that are most attractive for recreation as nesting sites. In winter, snow buntings are common visitors of the upper washlines.